{content note: suicidal ideation}

{another note: I wrote most of this piece before the COVID-19 global health crisis was being taken seriously within so-called canada. Meaning, the following exploration of the tedium and humiliation of disabled bodyminds, of moving through the city, through waiting rooms and appointments, and through unwanted conversations, happens before our late-Winter & early-Spring & however-long experiences of recommended or required self-isolation began. That’ll be explored in the future, though I can say now that the tedium, humiliation, unwanted conversations have increased, as well as the actual pain, and the rage and alienation I often feel with regards to non-disabled and non-sick people.}

{another note again: Interspersed throughout this piece are slightly-edited versions of shorter works I’d originally published as locked entries on my Patreon page.}

{and another note again again: I thought about words that convey the opposite of ordinary, and the opposite of humiliation, but I just haven’t been feeling it these days, so it seemed disingenuous to pretend that I am.}

At the pharmacy, I was thinking about the role of humiliation for disabled bodies, the unavoidability of humiliation. The day before, I’d called to have prescriptions refilled. They asked which ones. I told them whatever refills are on my file, but the two most important ones are Cymbalta and Seroquel, which I take every night. If I miss a dose, withdrawal happens immediately – I don’t sleep, pain increases, appetite diminishes. Then I become nauseous, then migraine, then bedbound. Then two or three days of sickness and recovery during which I am barely functioning.

Last time I’d seen my doctor was mid-December. I’d been instructed to return in a month; I’d been given two new prescriptions after a pinched nerve in my shoulder (after finishing this piece, I also pinched a nerve in my neck!), and my doctor wanted to know how the meds – Lyrica and Naproxen – had effected me. During that appointment, I’d told her that even when I’m mobile, even though her office is close to home, one reason I have a hard time making appointments and maintaining emotional equilibrium while I’m there is that there’s only one route to take, and the route begins by passing empty old rooming houses from which tenants have been or are being evicted, and then a long series of condos in the process of being built, altering the skyline, casting shadows, longer shadows each time I walk through, pushing out people who belong in the city but now have nowhere to go. I’ve been walking (or taking public transit, or taking WheelTrans) to her office for five years, and the neighbourhood becomes more hostile, more depressing, more frightening, every time.

{image description: Looking downward at my feet and cane on the ground. Concrete sidewalk, grey. Black boots, black tights, lavender cane. On the ground is a fallen flier. The Monopoly Game Man holds a piece of paper and a hammer. He stomps on houses. Text reads: I’VE SEEN THE FUTURE. I CAN’T AFFORD IT.}

She knew what I meant. I had a feeling I wasn’t the only client who’d told her this. From what I can observe from the waiting room and the pharmacy, the building she works in serves a variety of queer and trans clients, poorer people, and then a larger multitude of straight yuppie couples with babies and young children, too. The business next door sells furniture designed exclusively for new condos, and then there’s an overcrowded and underfunded dome-style homeless shelter two blocks away that the wealthy new residents complain about. One direction takes me to the financial district – the other direction takes me to the ODSP office.

{image description: Taken at the ODSP office. A corner, white walls. A notice that we’re on camera, under surveillance. To the right, a green and white poster for a scent-free environment. Text reads: “HELP US KEEP THE AIR WE SHARE HEALTHY.” Symbols below indicate: no body spray, no perfume, no scented hand creams or skin care products, no laundry detergent, no scented hair products, no air fresheners.}

Now almost two months (three months?) have passed, and I haven’t returned to update her on the med situation. As a doctor, I like her. She hasn’t been perfect, and she’s made decisions about my care that I occasionally resent, but she’s one of very, very few doctors who’s listened to me, affirmed my knowledge of my own body, and hasn’t shamed me or condescended to me. She also appreciates my strange sense of humour, and asks me about my creative work. Because it’s queer Toronto, we even have a few friends and acquaintances in common, though we rarely discuss this. My file is flagged for thirty-minute appointments instead of the usual fifteen because my bodymind can’t squish all our issues into fifteen minutes, I often spend a good chunk of time crying, and I can’t cope with health care spaces that push me out or require me to hurry and to show no emotion. She encourages me to take notes and to bring notes – something I’ve actually had professionals actively discourage, which is so dangerous, irresponsible, and invalidating. She’s seen me when I can barely walk the thirty feet from the waiting room to her office, which is more than most people in my life have witnessed.

She usually remembers my pronouns, and frequently corrects others.

{image description: Photo taken on a grey day. To the left, bare-branched tree lining the street. To the right, the edge of a grey building with a wheatpasted poster of a face emerging from a triangle, looking up as if lying down. Lips, nose, and eyelashes extend beyond the frame. The wall around the poster drips paint in rainbow stripes.}

{image description: A boarded up brick building. The small yard is contained behind a blue metal fence to deter trespassers. Red brick, two stories tall. A bit of snow left on the ground. Empty storefront next door. Black leather loveseat with polished wooden arms on the sidewalk. A black bag of trash in the snow.}

When I went to the pharmacy the next day shortly after noon, after having been assured my prescriptions would be ready in the morning, the pharmacist told me they couldn’t find them. I suggested they look under both M and E because often people don’t understand that Elizabeth is my last name, and things get misplaced or misfiled. They searched more and the meds weren’t there.

It’s a body-feeling before words that happens within me during moments like this. The frustration of how often it happens yet how unpredictable it is, how I see a task on my to-do list, Pick-Up Meds, and I forget to think ahead for potential mishaps, to prepare myself, to rekindle some kind of emotional fortitude before these kinds of interactions. To take a fucking Xanax. Meditate? When I’m unprepared for something so banal, so common, in a disabled life, I find myself blaming myself.

*

On an earlier night…

“Why are you here?”

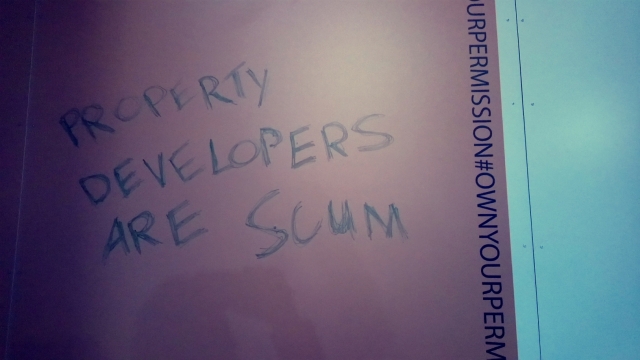

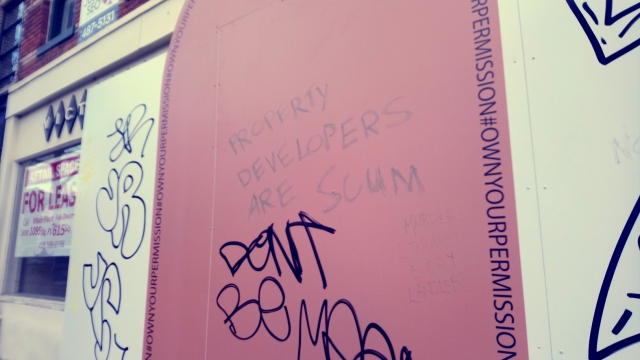

The night before the Full Moon in Leo, I went to a show. A friend from Montréal was staying with me for a few days, and after parting ways for the evening, we were meeting at the show late at night, with other friends invited, my partner at my side. Earlier in the day, I’d had an allergic reaction at the drugstore, so I was still coping with a headache, weakness, and a touch of nausea. Medicated, scamming a ride partway to the venue and walking the rest of the way. Along Ossington, another old building was boarded up and hidden behind a thin wall, the usual bold and austere branding printed on the boards. “You have PERMISSION to tag this wall.”

The structure was new – tagged only twice.

LANDLORDS ARE PARASITES.

PROPERTY DEVELOPERS ARE SCUM.

And I reached for the gold Sharpie in my coat pocket.

MURDER LITERALLY EVERY LANDLORD.

NO CONDOS ON STOLEN LAND.

At the venue, security at the door, two men.

“What happened?” one of them asked me.

“Open your backpack,” the other said.

My mouth dropped open, but I was silent. My cane. There were a lot of stories I could tell. I wanted to. I wanted to tell him stories and scare him away. Early childhood trauma, I could say, sexual trauma, long-term poverty…

I’ve provided these answers before, these answers and more.

My brain was scrambled at the nuisance of it, the obliviousness. Words wouldn’t arrange themselves into a coherent order. Instead, I was seeing these thoughts in shapes, colours, and scenes. Not words.

He searched my backpack.

“You don’t have to answer,” he said.

“I KNOW,” I snapped back.

One was silent, watching, the other uncertain what to say next. I think he apologized.

“I’m used to it,” I said. “It’s forever, if you need to know. It’s not one thing that happened.”

He told me to be careful – for the second time. The slippery floor. Be careful. I know.

Inside, I walked through gathering crowds to find the chairs lined up along the wall, to sit down and take off my Winter layers. My partner sat beside me. We put our handknit scarves, my earmuffs, into my backpack, already full of notebooks and pens and meds, etc.

My friend who was staying with me found us, and we hugged. She’d changed her outfit, make-up, hair. We talked about all the cute goths.

“I left my lipstick at home,” I confessed.

“Use mine.”

Earlier, we’d been talking about cheap make-up. At the drugstore, the drugstore where I had an allergic reaction, I’d purchased a different brand of liquid and powder foundation than the cheap Cover Girl I’d been using since I was thirteen. My blemished skin had improved within a day and a half. My friend lent me a tube of MAC lipstick with a matching lipliner, a shade called Sin, and I applied it in the dark bathroom. Truly higher quality than what I’ve been wearing the last twenty years or so. I only have one tube of MAC lipstick of my own. The last time my friend was in town, she told me she’d found her fancy purse in a dumpster. I told her I dumpster a lot, but I’d never found anything as fancy as her purse. Then I went downstairs to the basement bathroom at the bar we were at, and somebody’d forgotten their designer make-up bag filled with designer cosmetics. I swiped the lipstick and lipliner, classic red, a shade named Cherry, barely used. When I came back upstairs, I showed it to her.

I admired my reflection in the small, grimy, graffitied mirror.

{image description: Selfie in a dirty mirror, in a tiny bathroom painted black. My reflection is obscured by shadows and white Sharpie, though a light bulb glows down on my face, my pale forehead, my dark lips. Black floral dress, round glasses, unsmiling, looking to the side, toward my camera, half of which is also reflected in the small mirror.}

The first band, dregqueen, who my friend told me were friends with my twin, started their set, and I emerged from the bathroom, ambled back toward the chairs where my partner was waiting. We stood up and held one another. I could see my friend dancing and I wanted to dance with her, but my body didn’t have the capacity that night. One hand on my cane, the other on my partner’s back, underneath his women’s leather jacket.

Black, lace, leather, florals.

The singer and I had similar Hedwig and the Angry Inch tattoos. I mean, so many of us do. I appreciate these sightings.

I sat down between sets, rested. Sore hips, as always. Inner thighs feeling bruised.

When the second band, Cloud Rat, started, we stood again, dancing vaguely. I held a firm but flexible stance, space between my feet, swaying my hips, cane to the ground, holding hands.

One person tripped over my cane, passing from behind me to find a place to watch the band close-up. The singer was screaming.

No apology.

Next song, somebody else tripped.

Nothing, no acknowledgement.

A kick against my cane, brushing against my arm, my body not a body but an object like a pillar or a coatrack, stumbled into as if I/it were in the way. Nobody looked back to see what or who they’d tripped on. It was a surprise each time, each person tripping against me (tripping me, pushing me) before they were within my line of sight, over my shoulder, a dark, noisy space.

When the next person, fourth or fifth, turned back briefly and apologized (after their partner had not), I thanked them. Thank you, instead of my usual No worries.

A song or two later, the couple left. Somebody else tripped on me, silent still.

The couple returned. The first person, as before, tripped on me, and then their partner tripped on me again. It wasn’t a crowded show. It was dark, but there was space. Everyone was dressed in black in this dark space. My cane is lavender, not invisible.

This time, each of them apologized, only because I was startled enough to yelp, and this seemed to make them uncomfortable (actually, I’d inadvertently shout-mumbled a mantra I usually repeat in silence, internal, ELBOWS UP / ICE PICK OUT). Like being questioned at the door, when the couple apologized, again, I was blank. Thoughts forming but not words.

My partner asked me how I was feeling.

When I inhaled, when I opened my mouth to respond, I cried instead.

“I’m not okay,” I said. “I’d rather go home.”

{image description: Returning on a different day, more graffiti had been added to the so-called Permission Wall, the cringe-branding. Some of it is meaningful to me, the same anger. Others are disappointing, almost laughable. In this image, somebody has used a black Sharpie to write on top of ‘PROPERTY DEVELOPERS ARE SCUM.’ Now it also says, ‘DON’T BE MEAN.’ I imagine it written by a trust fund artist who’d call the cops on their noisy neighbours, don’t you?}

{image description: The same wall. FEELINGSBOI sits, holds their knees to their chest. Their speech bubble says, “EAT THE RICH.”}

{image description: Nighttime shot when the wall only had a bit of graffiti.}

{image description: Daytime shot from across the street, showing the wall built around a corner building, two-story brick, painted a green-y beige. More graffiti accumulating.}

Struggled back into my Winter layers, crying. Holding my partner’s hand and walking ahead of him, guiding him through the crowds and down the hall and past security and out the door. The cold, drunk night.

I waited outside while he briefly returned to the venue to explain to my friend what happened, a small change of plans. He’d bring me home to cuddle, and leave when she returned. We were sharing my bed.

Often, the feeling is I don’t belong. The feeling is I am being pushed out.

It was the night before the Full Moon in Leo. Full Moons, the day before and after, I am exhausted. It’s a pattern. I try to be alone or as alone-as-possible on Full and New Moons.

Often, the impulse is to hurt myself. The impulse is to quit.

Like, Fine then. I will never go to another show.

My usual fantasy. Stabbing with the ice-pick clipped to the bottom of my cane. On the feet. Puncturing boots, disabling those who can’t see me.

Most of those thoughts were gone by the time I came home, by the time I fell asleep.

Sometimes the thoughts are too redundant for me to knowingly choose to cling to anymore. As the weekend continued, I followed updates from the Unist’ot’en Camp, the RCMP raids, the red dresses, the solidarity protests. With traintracks blocked across so-called canada, my friend wouldn’t be returning home to Montréal when planned. Neither of us minded, both in solidarity. Friends at the camp with broken phones. We were given another twenty-four hours together before she boarded a last-minute Megabus home. She’d read the entirety of the copy of Bottle Rocket Hearts by Zoe Whittall that I’d lent her.

“What happened?” doesn’t mean what happened. It means “Why are you here?”

*

“My mouth dropped open, but I was silent. My cane… Stories I could tell… My brain scrambled at the nuisance, the obliviousness. Words refused to arrange themselves, incoherent. Instead, seeing these thoughts in shapes, colours, scenes. Not words.”

This is how I felt again at the pharmacy, how I responded. The familiarity of the feeling, the frustration of it, the exhaustion. Need my body always be a topic of conversation? A topic of conversation with/for people I don’t know?

They could fill my prescription for Cymbalta while I waited, but they couldn’t fill my prescription for Seroquel for another two weeks. The other meds weren’t mentioned and I wasn’t gonna bring them up. They kept reminding me about the option for free delivery, but most times I’ve used it, there’s been a similar mistake, a kerfuffle, and I have to wait at my window all day and feel crazy and angry about everything and then act very polite.

With my limited mobility, if I walk to the pharmacy and my meds aren’t there, I cannot simply come back later. How could I forget that one small task can take me days? What is it like not to have to take these possibilities into consideration? Do pharmacists know Spoon Theory? I briefly wondered.

I stumbled through language. Used words I try to avoid, like always and never. This always happens! It’s never easy! I felt irritable and short-tempered, and I felt like a rude customer, and I apologized as it happened, still unable to find the words I wanted.

“It’s not personal, it’s just that every time I come to the pharmacy, I feel like I’m not-a-person.” Exasperated. I made a self-deprecating joke about not having taken a Xanax before coming down.

I stuffed the pill bottles into my backpack, put my mittens back on, and my partner and I left, walked to his place.

Back at home that night, late, I took the bottles from my backpack. Childproof caps, despite a request/demand on file for the last five years to use easy-open caps. Wrist-pain. Usually they forget. If I’m picking up my meds at the pharmacy, I’ll check, and then I’ll ask them to replace the caps. If it’s a delivery, I’ll remind them on the phone, but they’ll still sometimes forget. This time, I felt so flustered and aggravated, I forgot to check at all. The bottles were different sizes from the previous ones, so I couldn’t switch them on my own. Instead, I poured the pills into a Ziploc bag.

Another day, when I went back for the rest of my meds, the same thing happened. But I remembered to check, asked them to fix it.

*

The exhaustion of my body as a constant conversation. A conversation that changes within myself, but not without. An understanding of my body that others can’t see, or understand, or imagine. A confrontation with my body, a confrontation with non-disabled bodyminds, with professionals, with power, with paperwork, with permission.

A week or two earlier…

{image description: Looking downward at my feet at the ground. The sidewalks are snowy. Black boots, lavender cane held in my left hand, a TTC token between my forefinger and thumb. Fuchsia floral dress below-the-knee, black & grey-striped wool socks. A deep violet and forest green checkered wool coat. Black lace tights over fleece-lined purple tights.}

I was meant to have a phone date with a friend at noon and a meet-up with another friend in the evening, but the latter was canceled due to conflicting schedules and the former forgotten, didn’t respond to my texts. I didn’t feel let down this time. I was aware of so much else that needed to be done – when I think about every task, every appointment, every sheet of paperwork, every text and letter to respond to, my breath becomes short and shallow. Aside from my social plans, I wanted to write.

I don’t forget that I have chronic fatigue (I accidentally typed chaotic fatigue, which is not untrue), but I do forget to structure my life such that I’m taking my spoons seriously, and that time, more time than “normal”, is set aside for rest.

Maybe that’s it, the idea of setting time aside, instead of being within that time. Something else I hadn’t thought until I typed.

The day before, my planner said Rest. The day before that was intense. I’d participated in a day-long Imbolc ceremony, ending with me and thirteen others gathered, burning our prayer sticks in a small fire as we stated our intentions, a distillation of messages that had come to us throughout our discussions, meditations, and prayers. A new intention I’ve been repeating to myself each day since. I knew I’d need to sleep. There’d been a blustery storm. I was glad for the snow, the beauty of the snow, as there’s been so little in the city this season, but when I walk through it, my body requires more rest. So I didn’t set an alarm. I gave myself permission to sleep.

I was in bed after midnight and asleep until 1:30 the next afternoon. I journaled throughout the day, and I did nothing. I allowed myself to absorb wordless feelings, to not think about what’s next, what’s owed, etc. I was still drinking my “morning coffee” as the sun set, and I was ready to go back to bed at 10PM.

One of the many tasks on my to-do list was to contact ODSP (Ontario Disability Support Program) since I’d noticed that one part of my monthly allowance hadn’t been deposited into my account – the part that covers transit fare. I could’ve called them but it’s notoriously impossible to get through. I had mail to send, so after the post office, I went to the ODSP office. I hadn’t allowed myself to overthink it the way I often do, and I’m glad I didn’t, but that also resulted in not thinking ahead to take a Xanax, which I usually need to do for appointments in hostile or otherwise stressful settings, especially institutional settings, as with the not-yet-happened pharmacy incident described above.

Short line-up. I waited with the others. I stretched my sore legs, bent my sore hips. Looked around me at the posters on the walls, the notices of surveillance cameras, the frosted glass walls and closed doors. Framed paintings of city-scenes. A streetcar at night. The pain in my hips, thighs, and the backs of my legs increased, not necessarily from walking and then standing in line, but from the environment itself. I could crouch down to the floor as I have in the past, as I had around the fire on Sunday night. What stopped me.

When one of the receptionists called me to the desk, I explained my situation to him. I asked him if I was supposed to see my doctor and fill out forms again, or if I’d be able to talk to my caseworker and have the allowance approved of an reinstated. He told me I’d have to make an appointment with my doctor, have her fill out the forms, then deliver them to the office. He asked me when I needed the money.

“I need the money four days ago,” I said.

He asked me for ID.

Apologized for the time it took him to find me in the system.

“I spelled your name wrong,” he admitted, passing the card, the card where my name is spelled correctly, back to me. “I’m used to it being spelled M-I, not M-A.”

“It happens a lot,” I said, sliding the card into my wallet. “Maranda with an A, like Anne with an E.”

He was silent, then turned back to the computer screen.

I have a friend who invites me over to her place late at night, where we entangle ourselves together in her bed and watch Anne With An E, as many episodes as we can until our eyes will no longer stay open, until I know I’ll be a little bit sick the next day from staying up too late, taking my meds too late. We’ve promised to bring our Anne dolls with us next time, hold them while we watch, go to a thrift store together to find Anne dresses to wear. We always cry.

I was standing alone in the ODSP office making an Anne of Green Gables joke that nobody understood or cared about.

The receptionist told me he was uncertain after all. I should talk to my caseworker. He left a message with her, and I retreated to the waiting room, took a book out of my backpack to keep me company for the wait.

During the Imbolc ceremony, I’d talked about how reading Anne of Green Gables as a child might’ve been my initial foray into spirituality, how the character Anne Shirley-Cuthbert is still an obsession of mine, an influence.

I read three or four pages until a nearby door was opened, and a caseworker stepped out.

“I’m looking for somebody named… Maaarrrraaandaaaa…?”

“That’s me.”

Picked up my stuff, came into Interview Room #3. Sat across from one another at a large, empty table. Explained my predicament.

I was wearing my Winter layers, my backpack unzipped on the table, a black pen and the book I was reading placed beside it. Prostitute Laundry by Charlotte Shane. Red letters.

The caseworker assured me she’d have the money deposited into my bank account within two to three days. She told me to have my form filled out by my doctor, yes, but in the meantime, the transit fare allowance would be deposited into my account for the next three months.

I was kind but I must’ve appeared stressed. Flustered. Asking questions, voice shaky, scattered. I’d been through various forms of this process with her in the past. She didn’t remember me. Understandable. At the ODSP office, we are numbers. Often, we are numbers in distress. Beside the name on our forms, we’re required to write our “Member ID.”

We’re asked for our “Member ID” before our name if we get through on the phone. I’ve been on ODSP for thirteen years, and I won’t write it down, won’t remember it.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m not here to make you feel anxious.”

“I know,” I said. I remembered meeting her two years ago, a kerfuffle over the same allowance, the missed deposit with no notification in the mail. The same old common disasters of social assistance. “It’s the building, the space, the architecture that stresses me out. It’s the system that makes me feel anxious, not necessarily the individuals I interact with while navigating it.”

After our brief meeting, I sat in the waiting room for another few minutes. Assessing the situation, my mood, the relief of not having to fight so hard this time (just kidding – after writing this, part of the allowance was denied after all, and I have thirty days to request an appeal…). I took a selfie, and I texted a friend who’d also recently dropped by the ODSP office and texted me from the waiting room, telling me they literally wanted to die. Their partner was with them for support.

From there, I walked to the library. There were more errands to do, but I needed to sit, to rest.

At home in the evening, radio on. Getting ready to go out again, this time to a Thai Restorative yoga class.

Listening to After Dark on CBC. As I reach toward the volume to turn it down before leaving, Odario Williams, the host, says, “If you need permission to do nothing, here it is. Even if it’s just for one song. Listen to this song and do nothing.”

P.S.: If you’ve benefited from my writing in any way – if my words have inspired you, helped you feel less alone, or sparked some weird feeling within you; if you’ve felt encouraged, or curious, or comforted – please consider compensating me by offering a donation of any amount. Whether you’ve been reading my writing for years, or just stumbled into me this afternoon, I invite you to help me sustain the process! ALSO! I have a Patreon now! Please join me.