A few months ago, I was hanging out with a friend of mine, and on my way out, she told me to bring a bag of potatoes home with me. One of her roommates had purchased their weight in potatoes as part of a performance art project, and now that the performance was over, there were hundreds of potatoes in their home. I didn’t see the performance, but I appreciated the way that their art had also become a means of distributing food to hungry friends.

crip food

These are the kinds of moments I come back to each time I see these stories of wasted food during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the photos commented on frequently was that of thousands and thousands of potatoes destined for the garbage now that restaurants aren’t buying them. I wondered: How come there isn’t an infrastructure either already in place or currently being created, to ensure that these potatoes, and all the other wasted foods we keep hearing about (not to mention those we don’t hear about) are redistributed to those in need? Why let them rot when you could give them to people who’ve lost their jobs and lost their incomes, lost their homes, give them to food banks and other free food/meal programs, what about building larger-scale Food Not Bombs collectives, etc etc…? In a society where profit weren’t priority, what would the possibilities of food become?

Questions like these have been asked for generations. But the old maxim, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, remains true. (What about the rich get eaten and the poor get fed?)

When restaurants, cafés, and bars began to close down, one of the first things I thought about was how dangerous dumpsters would now be, and then, how empty they now are. A couple years ago, most of the food I ate was rescued from dumpsters. The city has thousands of free meals on offer every night, as long as you know when and where to look, as long you have the right mix of courage and desperation to go out and dig, and as long as your body can perform this labour. Living on my own in Toronto, this became a frequent ritual for me. When I lost my ability to carry anything, and then my ability to walk, I also, of course, lost access to those dumpsters, and I didn’t have friends or a community who’d do that weird but necessary labour of reclamation for me. During a state of remission, after I’d lost handfuls of friends, and eased into a different sense of self, I returned to the dumpsters. Ones I’d known in the past, and unknown ones I continued to seek. As I entered a new relationship, I found that skulking about at night in search of free food was a favourite activity we shared, and so we became raccoons together at night, learning the alleyways and trash bins of multiple neighbourhoods, and keeping ourselves well-fed. Occasionally, we’d encounter others. Share a few words, share food, move along.

There is always some risk in this activity. And in recent months, dumpstering came with the possibility of contracting a severe and potentially deadly illness. The last time I took home food from a dumpster was my last time for a reason. The state of remission I’d been in, which feels like a longer time ago than it was, had been dissipating. My body was holding more pain, which meant I couldn’t carry the weight of food, nor do the labour of digging, cleaning, organizing, storing. My lactose-intolerance had worsened, so I had to avoid dairy again. The thrill of gathering free food wasn’t the same when I knew how sick it’d make me, and on a more personal level, I had so many memories of dumpstering with my now-estranged-ex, that often the activity would leave me feeling unbearably melancholy. There were neighbourhoods I wouldn’t forage anymore, and risks I’d no longer take.

When I brought home my last bag of dumpstered food, which was heavy and awkward to carry, I was alone. I’d dumpstered at the same place many times before and never had a problem. But this was my night of bad luck. I happened to have brought home the bag that had been poisoned. I’ve always known this could happen – this aversion to giving people food for free, choosing to leave it in trash bins instead of donating it, is not news to me. The food in this clear garbage bag, which seemed ordinary and familiar at dusk, I realized at home, had been made toxic with an uncoloured cleaning product that wasn’t obvious to the senses until I’d really dug in. The pain in my body, and the sick-headache-feeling, the gagging, the vigourously brushing my teeth three times to rid my mouth of the chemical-taste, wasn’t a risk I wanted to be forced into anymore. While a kind of despair has always come to me through trash, there was pleasure and joy, too. Those feelings had diminished, though. While I didn’t and don’t want food to exist for profit, this alternative felt less tolerable, too. The act itself, the ritual, had been nourishing, if exhausting. Now there was a lack, an emptiness, a different kind of worn out.

***

I’ve been having most of my groceries delivered for years. At my sickest, when I was unable to walk or to go outside (I couldn’t even cross the street on my own; I needed my then-partner to help me, and this meant slowing down traffic even on the one-way residential street where I live. I could also barely cross at intersections with lights because the walk-light wasn’t long enough for my slow, crooked body), I made countless agonizing and crazy-making phone calls to food banks, CSA’s, and the like, asking about food deliveries. This was a service that was not available. I found absolutely nothing and no one. I remember the infuriating frustration, the trapped feeling. I remember feeling so enraged and fucked up, wanting to burn everything down, screaming alone in my apartment.

Now these services are (temporarily…?) being offered, but I can’t get an order through because all the time-slots are taken. Between big-box stores like Walmart, which I frequently rely on (wah wah), and local services with a focus on social justice making boxes of fresh, local produce, I either can’t get through, or am waiting up to two months for food and other basics to arrive. I have a (different) partner getting groceries to me, but we’re stuck making more trips outside than we ought to be during a pandemic.

At my sickest, it took me hours to get my delivered groceries from my own door to the kitchen. At my sickest and most debilitated, I didn’t enter a grocery store for OVER A YEAR. Sick and disabled people are being left behind again.

In so-called canada, those of us on social assistance are paid the final day of each month. That means the second last day of each month is when we’re the most broke. Sometimes I imagine a world where small facts like these are known and considered and respected. That in the early days of each month, people who weren’t on social assistance knew to stay the fuck out of our way.

{image description: Green grass takes up the entire frame, with a white circle spraypainted through the middle. These social distancing circles have been painted throughout Trinity Bellwoods Park, the neighbourhood where I live. The first time I saw them, I imagined altering them to pentacles, anarchist circle-A’s, etc. The next time I went out, somebody had! Image shows a single circle which has been redone with more white spraypaint to make a pentacle large enough to lay down and spread out within.}

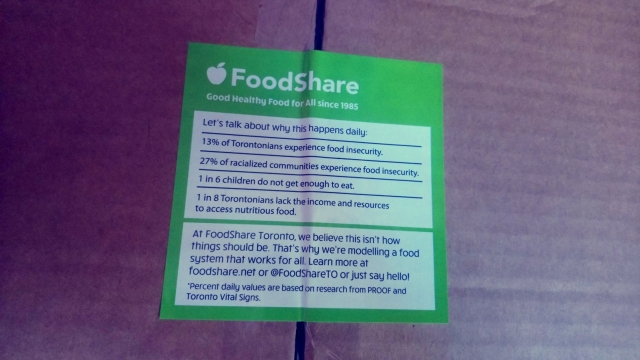

{image description: A green and white square-shaped sticker on a sealed cardboard box, close-up. After writing this entry, I was able to connect with FoodShare and signed up for weekly deliveries of produce delivered to my door. $18.50/month. Sticker reads:

“FoodShare. Good Healthy Food for All Since 1985.

Let’s talk about why this happens daily.

13% of Torontonians experience food insecurity.

27% of racialized communities experience food insecurity.

1 in 6 children do not get enough to eat.

1 in 8 Torontonians lack the income and resources to access nutritionous food.

At FoodShare Toronto, we believe this isn’t how things should be. That’s why we’re modeling a food system that works for all. Learn more at foodshare.net or @FoodShareTO or just say hello!

*Percent daily values are based on research from PROOF and Toronto Vital Signs.”}

{image description: A handmade Black Lives Matter banner affixed to the fence surrounding the tennis courts in Trinity Bellwoods Park. “Black Lives Matter” is stitched patchwork-style, black letters on white fabric, and various symbols are illustrated around the text: a Black Power fist, a burning candle, a cop with a pig’s head behind bars, angel wings, rainbows, hearts, flowers, etc. In the background, the sky is pure blue, cloudless.}

{image description: A Parkdale storefront, Black Diamond Vintage, with BLACK LIVES MATTER large paper-letters taped to the window, surrounded in Black Power fists of various colours. Brick walls are painted black, orange, and pink.}

{image description: Next door, another Parkdale storefront, Bone & Busk, has red letters in Gothic script painted on the windows. GOTHS AGAINST FASCISM. Beyond the glass, three otherwise nude mannequins wear black fabric face masks that read BLACK LIVES MATTER. On the right, a lavender door hangs open.}

{image description: The large intersection of Queen West and King / Roncesvalles in Toronto. Roads are much emptier than usual. Brick buildings on the corner with large billboards on the rooftops. Usually these billboards show what movies are currently in theatres. Now they are blank. One billboard is white, the other is black. Above the intersection, electric cords connecting the streetcar system criss-cross in a tangle mess. Skies are pure blue.}

{image description: Close-up of a black and white poster taped to a hydro pole. Three black flags read in allcaps: END POLICE BRUTALITY. BLACK LIVES MATTER. NO JUSTICE NO PEACE.}

{image description: A wide, squat brick building painted with a gorgeous portrait of Frida Kahlo with the wings of a monarch butterfly. She wears dangling earrings shaped like hands. Background is painted sky blue with cactuses. Black letters to the left read:

“Pies para que los quiere,

Si tengo alas para volar.”

Google translate says:

“Feet so you want them,

If I have wings to fly.”

Which is actually:

Feet, what do I need you for

When I have wings to fly?

The mural artists are MSKA and Anya Mielniczek.}

My time in Toronto has taught me that I’m unlikely to survive an apocalypse. I know we cannot be self-sufficient – I cannot be self-sufficient – but its opposite, interdependence, hasn’t been consistent enough to be relied upon. Multitudinous apocalypses have occurred – consider Black people being enslaved, consider genocides of Indigenous people, consider histories of eugenics and forced sterilization – and continue to occur – consider what that previous list has led to today – and someone in my socio-political position is sometimes but not always a target, directly or indirectly. Sick and disabled people are frequently left behind. Those of us on social assistance are forced to starve, forced into social isolation, forced into underground economies and other crimes-that-shouldn’t-be-crimes to ensure our own survival.

I still imagine what would be needed to survive, what could be created. I imagine wanting to be in the mess.

What makes you want to stay in the mess?

***

As always, my thoughts are turned toward those of us on social assistance, including those involved in underground economies, and those who aren’t or can’t currently be engaged in said economies – be it sickness, self-isolation, danger and risk, etc; and those who continue to work, at heightened risk, for lack of choice. As benefits and bail-outs are announced (and altered and struggled with and fought for and and and), we find ourselves forgotten and left behind again and again. Like workers, and yet so unlike workers, too, we are the expendable, the discarded.

{image description: Me, standing in front of boulders that are taller than me. The boulders have mosses growing all over them, various shades of green spreading over rocky greys. My left hand reaches out to hold one, while my left hand holds my cane. The forest floor is covered with dead, browned pine and cedar sprigs and bare, fallen branches. Dozens of said trees grow behind me and the boulders. I’m wearing a below-the-knee black & white floral dress, plum tights, black boots, and a brown-ish plum tweed blazer with a wraparound scarf of black & violet damask. My hair is below-the-shoulders, long, purple. I’m smiling.}

{image description: Camera aimed down, showing my feet on the ground, dead leaves scattered. My left hand holds my cane, as well as a collection of bones, belonging to a deer. Found amongst another gathering of mossy rocks.}

{image description: Another view of my feet and my cane. This time, I’m standing in line at a grocery store. The floor is grey. I’m wearing loose-fitting high-waisted black shorts over black tights with black boots. There’s a round blue sticker on the floor with the shape of a set of feet in white. It reads: “Social distancing. Please stand here.” A red line is taped to the floor.}

{image description: Empty branches of vines grown across an unpainted wooden fence. An old, clear Christmas tree bulb hangs from the vines in the centre of the frame. The thin branches behind and around the bulb look like an anarchist circle-A.}

crip rent

On ODSP, we receive a maximum of $497/month to cover rent, forcing us to forfeit our so-called ‘Basic Needs’ allowance to landlords rather than our own safety and well-being. As calls for rent strikes were/are made, one of my first thoughts was how this could impact those of us on social assistance, what solidarity with us would/could look like, and what our solidarity with workers suddenly without jobs or wages would/could look like. A rent strike for folks on social assistance, especially those of us with mental illness and/or chronic pain and limited mobility, poses different kinds of risk than it does for working people, than it does for non-disabled people. We are under a different form of surveillance, relentlessly scrutinized, constantly under threat. On social assistance, the threat of review, of cutbacks, is ever-present. We are frequently required to re-apply for benefits already granted, to make doctor’s appointments, check-ups, to have the same forms signed again and again – many of us have lived through medical trauma, trapped in an inadequate system, ours bodies and minds examined and re-examined by countless specialists, countless machines. To be in constant approval-seeking mode in such an invalidating system, while attempting to resist the same system is an almost untenable paradox.

In my experience with organizing, including with anti-poverty groups, as well as my witnessing from over-here, in my day-to-day life, people on social assistance, especially sick & disabled people, have been forgotten and/or left behind again and again (I’ve said it so many times, and it never feels like enough, trying to communicate the emotional physical psychological spiritual impacts of this continual wish others have that we cease to exist, cease to remind them of our existence). Rarely acknowledged, rarely listened to, including and especially by working-class communities and organizations (who often don’t want to talk about ableism, don’t want to fathom the non-working, and will prioritize workers over sick and disabled folks, regardless of the obvious-to-some connections between capitalism, how capitalism can sicken and disable workers and others, how those of us on social assistance can and do embody the idea/ideal that labour enacted does not equal value of said person etc etc (run-on sentences on difficult to articulate things, yes please), and how some of us, through our illnesses, have managed to, in some ways, escape a system that only values us as labour performed, hours worked, and are now building our own worlds. I watch it happen and feel it happen. Try to notice when I am being left behind, and when I am choosing to leave of my own accord.

Anyway, as April 1st approached, I wondered how or if to participate in the rent strike. I’ve been in unstable housing situations much of my life, and lived in a lot of neglected little corners. I’ve been illegally evicted, I’ve been threatened, I’ve had homes that cave in and flood and remain in disrepair. I’ve had homes that grew moldy and made me sick, I’ve had screaming matches with landlords, I’ve had landlords who tried to tell me I couldn’t have overnight (I accidentally wrote ‘organized’) guests and couldn’t even burn a candle. I’ve been in shelters, I’ve been a teenage and even pre-adolescent runaway… The building I currently live in has a number of tenants on social assistance – some of us are pals, some won’t make eye contact with me, blah blah. Organizing would be made difficult due to the fact that one of the “tenants” is the landlord’s son. I rarely call about having repairs done to my home because a) I try to avoid my landlord and avoid confrontation as much as possible, and b) the contractor who works for the landlord has asked me out on dates in gross and inappropriate ways, so I’m uncomfortable when he’s around.

I had a few conversations with friends of mine on social assistance, including one of those who lives in the same building as me. What came up most often was support for tenants striking, with the knowledge that we can’t be included because we know we won’t be supported, we know the risks are more severe for us, and we don’t trust organizers or striking tenants to have our back – not in a significant or material way. (Actually, in the time it took me to complete this piece, one of those tenants left because she could no longer cope with the state of disrepair, the broken plumbing, the cockroach infestation…)

W

hen I brought up these concerns and more with one organizer, who asked for my input after reading some of my tweets on the #KeepYourRent hashtag, I received no response. That was almost a month and a half ago (I write on crip-time. As I finish this piece, we’re three months in, no response). When friends check in with me to ask if I’ve heard anything, if any kind of conversation has happened, I tell them no. Obviously they’re not surprised. We are familiar with this kind of let down.

One way to participate in the strike that occurred to me was: since ODSP offers a maximum of only $497 per month for rent, we could pay this much to our landlords, and keep what remains. In this way, we’d be in solidarity with other tenants on strike, and we’d be making a point not only about how unliveable our social assistance income is, but how absurd it is that what little money we have must be forfeited to landlords – the wealthy, the owners of property, those who profit on the human need for shelter, those who neglect the maintenance of the buildings we reside in while taking more and more and more, ensuring, for some of us, that we will be too sick and tired to fight, and too afraid to fight.

I’m not sure how effective this tactic would be, and like I said, I don’t trust anyone to have our back. I mean, I don’t trust anybody to resist our landlords with us, to fight for a raise to social assistance rates to the actual cost of living, to come to court with us if needed, to make sure we get fed and cared for in the meantime, etc. It’s difficult to imagine sustained support, especially beyond slogans.

{image description: An alleyway garage painted forest green, peeling, revealing brown paint on old clapboard. A sign is stuck to the door with black electrical tape. It says, “YOU ARE ON CAMERA. STOP DUMPING.”}

{image description: An alleyway brick carriage-house, bare branches of vines creeping across the walls. A yellow sign affixed to the brick reads, “NO DUMPING. Offenders will be prosecuted and a fine imposed.” The bottom of the sign is obscured with graffiti and ivy.}

{image description: A close-up of the old brickwork of said carriage-house. The right side shows details of the corner of crumbling bricks, the leafless vines, the brown metal drainpipe screwed to the wall. Left side shows the concrete alleyway stretching ahead, lined with garages. A figure is seen from the back, walking ahead – my partner, thin and tall, dressed in all-black. Black skinny jeans, black boots, black leather jacket, black hood against the collar, carrying a black totebag. He has long, wavy brown hair, about shoulder-length, side-parted.}

{image description: A brick wall at the end of the alleyway, painted first with a mural, then with graffiti, colourful layers. The mural has a butter-yellow background, with a figure standing in the middle, head unseen, wearing a pink party dress with a purple bow around the waist and matching purple knee socks. To the left of the figure, a bunch of pink and purple mushrooms are growing, with black-and-white-striped stalks. Swirls of graffiti tags in black and blue have been painted over and around the mural. White letters in a black bubble read: FUCK THE WORLD.}

{image description: Clusters of sweet violets growing low to the ground, little petals of bright purple with round green leaves. Grass, bare dirt, and dead leaves fallen last year, are visible. The flowers are of the ‘volunteer’ variety, likely transplanted from the mouths or paws or beaks or scat of local squirrels or birds.}

Beyond the risk of harassment, intimidation, eviction or attempted eviction, another risk of my idea re: how to rent strike on social assistance, is this: If an individual’s caseworker became aware that a recipient of social assistance were withholding rent, they’d be required to pay it back to the Ministry of Social Services. This doesn’t happen voluntarily, and I don’t know what a refusal to do so would look like or entail. Instead, the amount withheld from the landlord would be garnished in monthly increments from one’s paycheque until the full amount has been returned. Assuming the difference was spent on food and basic necessities – or spent on whatever, regardless – the recipient would now be even less able to afford rent and basic needs during the time their cheque is being garnished. I’ll let you imagine the consequences…

To clarify, I’ve watched this happen to friends of mine. It’s despairing, infuriating. I’ve also come under review in the past, and had my income abruptly suspended, which staff later realized was due to misfiled paperwork, not a legitimate disqualification for resources. I was forced to crowdfund what I needed to get by, during a time when I was mostly immobile and obviously in distress, but most people don’t have that option. I’m likely one of very few ODSP recipients who has a small following through their writing, art, or activism, as well as friends near and far made through half a lifetime of writing zines and corresponding with pen pals.

For myself and so many others, countless others, the next steps after eviction are homelessness and death. That’s it.

We’re accustomed to “choosing” shelter over food. We’ve been forced into this life with little chance of exit without a real revolution.

In the late-90’s, under the Mike Harris government, social assistance rates were drastically reduced. People died. In the time that I’ve been on social assistance (Winter 2007 – present), our income received a 1.5% annual increase, equal to about $8 – $12 / month, significantly below the rate of inflation. In 2018, we were due for a 3% increase for the first time – but the Ford government, now in power, scaled it back to 1.5%, and then canceled the raise altogether. Now, not only are we are at a standstill, but this Spring, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ford government also cut back the public transit allowance that some of us, including myself, receive by $50.00. Poorer and poorer as the rich get richer, forced to eat less, access less, suffer more.

As so many cuts were made under the Ford government, mass protests were organized. Thousands and thousands of people showed up. Except for when we organized against cuts to social assistance. Then we were lucky if twenty people showed. We are nothing and nobody – I understand that those of us on social assistance are seen that way. Nothing and nobody. Waste, worthless.

To the reader who doesn’t relate, who doesn’t know what this life is – what I say is not meant in an accusatory tone, but merely to offer a brief glimpse into my/our well-earned weariness and wariness around community support and solidarity. Our cynicism. Reasons we talk to each other, poor and broke sick and disabled folks, rather than to those outside our worlds, those who lack the experience and perceptions that we do, the knowledge that we do. We’re used to being left behind, especially during the crucial long-term.

Friends have been supporting #KeepYourRent, #RentStike, #CancelRent, etc., as they can – sharing on social media, printing posters for their windows, etc… But I’ve encountered no one who feels safe enough to participate on April 1st (nor, as of this writing, May 1st… or June, or July…). It’s unsafe for everybody, of course, and there will be long-term consequences for everybody. But it’s important to emphasize that those consequences are uniquely dangerous and potentially deadly for social assistance recipients. We are also concerned that we can’t actually confront, so to speak, our landlords in groups, not only due to COVID-19, of course, but also due to aforementioned sickness and disability, inaccessibility, etc. Myself and many of my friends are also at a higher-risk, due to our compromised immune systems, malnutrition, and other ordinary hazards and humiliations of being sick, disabled, and poor. Our instability and precariousness – of home, body, mental health, income – is shared with working-class folks, but also uniquely and excruciatingly different.

There’s a lot more that could be said, more questions to be asked. I do support strikes, and I hope they lead to long-term change. Over the years, and especially in the organizing and art-making I was/am involved with since the Ford election, when there were calls for general strikes, I often asked questions like: What does a general strike look like for people on social assistance? Who cannot or do not work? And what would solidarity with us look like? At the same time, as more and more people were calling for a general strike, the cuts to social assistance were still rarely, if ever, mentioned. We wondered who would strike on our behalf, and how. Concrete answers to these questions never came about. All the dreams that come from the questions are necessary, too, but tangible, direct action and support has been rare.

When I ask about solidarity, and dream about solidarity, I don’t just mean during the coronavirus pandemic, I don’t just mean during elections – I mean during the everyday, and into futures. Long-term, unimaginable futures. I mean through climate chaos and economic collapse. Solidarity must be creative and can’t be done begrudgingly. What are we upending? What are we building?

{image description: My cat, Lily, taking a nap on the accessibility chair in my bathtub. The chair is grey. Lily is a pale ginger, quite chubby now, so that his body takes up the entire seat. To the left, the shower curtain is visible – clear with purple, pink, and green polkadot pattern. To the right, white tiles.}

Though my writing is not meant to convince non-disabled people or working people that I have a right to exist, that my life is worth living, that I want to live, I do encourage those who are not on welfare or disability to consider those who are, and to consider the possibility that they might one day be, too. (In fact, that is one of the many possibilities happening now for so many people during the pandemic, and it will continue afterward.) If you don’t know anyone who’s on social assistance, or you don’t know what our lives look like, I invite you to ask yourself why. If you are on social assistance, I love you.

These are conversations that can be dangerous to have in public, by which I mean, online. Those of us on social assistance, those of us who refuse subjugation and refuse to be disregarded and discarded, are already both invisible, yet targeted at once. What options, what possibilities, do those places afford to us?

I dream of worlds without landlords. Worlds where nobody profits from the human needs of shelter and food – especially on stolen land. I imagine construction workers going on strike, urban planners and architects and public transit operators going on strike, refusing to work until all new homes built are accessible and affordable to very-low-income people, until public transit is free, until social assistance rates are adequately raised. I dream of each person finding a role and purpose within these kinds of strikes, and I imagine all of this happening in solidarity with LAND BACK, a call that has been made for generations, and happening in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, too.

I’m writing and living in solidarity with sick and disabled queers who’ve devoted time, even years, to attempting to build mutual aid networks and wound up with little, or with scraps, or with literally nothing, watched as their friends and communities faded away. Solidarity with those who are incensed and irritated when they hear/read well-meaning advice on self-isolation from people who aren’t sick, people who haven’t experienced limited mobility, chronic pain, the ordinary isolation of a disabled life. Those who now cringe when we read terms like ‘mutual aid’, terms like ‘support’. Those overwhelmed with memories of our struggles met with silence and indifference. Those, like me, re-visiting feelings of anxiety, anger, loss, and alienation. Those grieving. The unrecovering.

Those with few, if any, avenues for catharsis, for healing. Those in complex situations, those who will never receive apologies or resolution.

Nobodyingly Yours,

P.S.: If you’ve benefited from my writing in any way – if my words have inspired you, helped you feel less alone, or sparked some weird feeling within you; if you’ve felt encouraged, or curious, or comforted – please consider compensating me by offering a donation of any amount. Whether you’ve been reading my writing for years, or just stumbled into me this afternoon, I invite you to help me sustain the process! ALSO! I have a Patreon now! Please join me.